LRA-Funded Scientists Command Attention at 2019 ACR/ARP

LRA-Funded Scientists Command Attention at 2019 ACR/ARP

November 14, 2019

The Lupus Research Alliance was proud of the unprecedented number of the studies supported by the Alliance chosen for presentation at the 2019 ACR/ARP Annual Meeting, the world’s largest rheumatology conference. A total of 19 studies were shared in oral presentations to large audiences, while 13 were presented as posters, which allow for informal exchange among colleagues.

Here are highlights from emerging foundational research presented at the meeting:

Why Kidneys Get out of Synch in Lupus

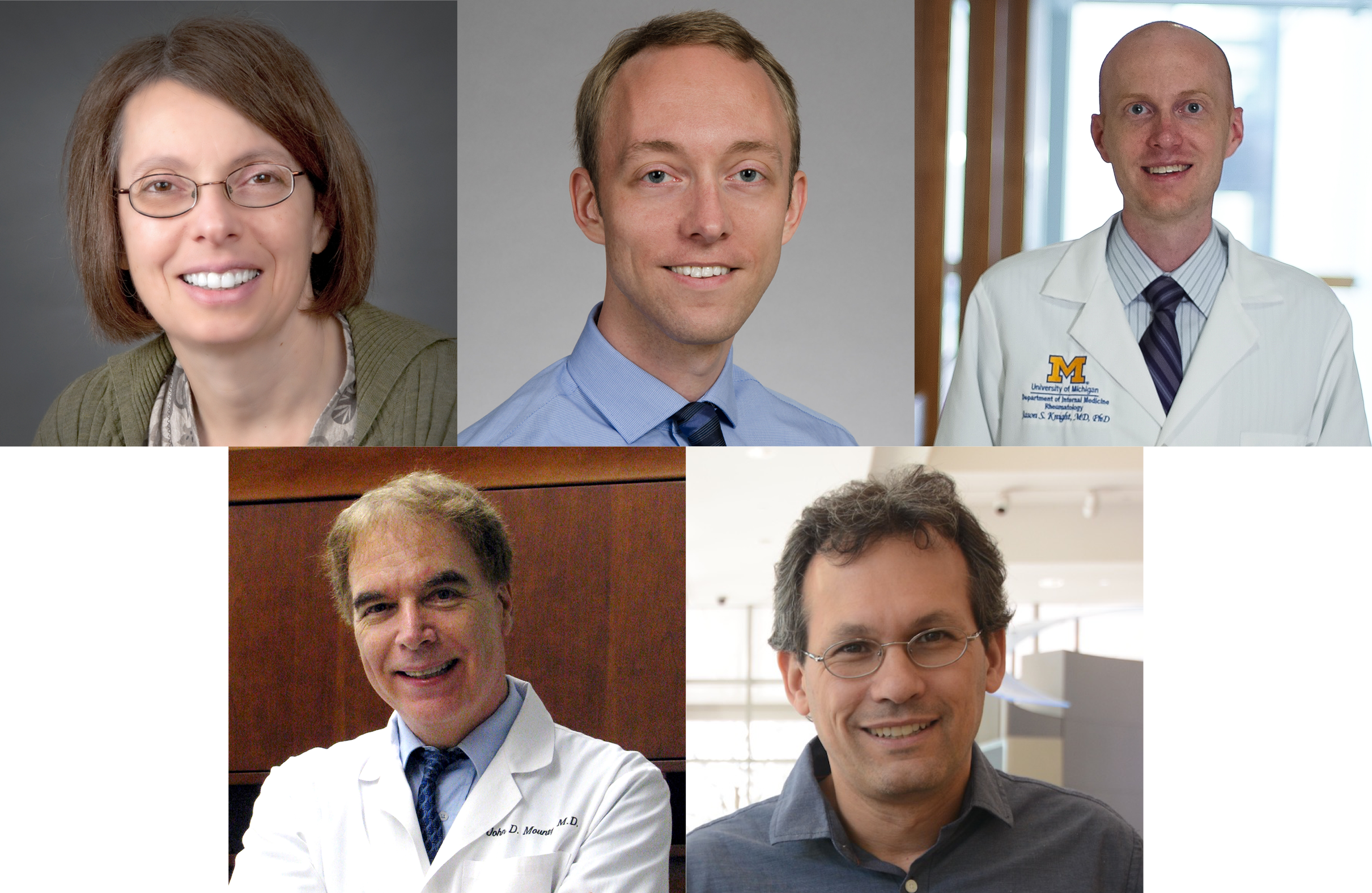

Our blood pressure and body temperature tend to be higher during the day when we are awake, and lower when we are asleep. The kidneys also follow a 24-hour cycle, filtering more blood and making more urine during the day than at night. By studying mice with lupus, Dr. Anne Davidson, of the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, and her team found that abnormal kidney rhythms can lead to health problems. For example, they observed that the blood pressure in mice with lupus did not go down when it should have. We know that people whose blood pressure doesn’t decrease at night are more likely to develop heart disease. The researchers found that they could correct some of the kidney changes by giving the mice a combination of treatments. See Abstract

New Insights May Lead to New Ways to Curb Disease Flares

Two studies presented discoveries about the webs of DNA that some immune cells release. These webs, known as NETs (neutrophil extracellular traps), trap bacteria in healthy people and protect the body against infections. In lupus, however, NETs may stimulate the immune system to attack patients’ own tissues.

Dr. Christian Lood of the University of Washington and his team identified that the levels of NETs in the blood may predict whether patients will have disease flares. The scientists found that patients with lupus had more NETs in their blood than people who do not have the disease. Patients with higher NET levels didn’t necessarily have more severe symptoms. But they were more likely to have a disease flare within the next few months. Dr. Lood concluded that doctors may be able to use NETs to identify patients who are vulnerable to flares and begin treatment early. See Abstract

In another study, Dr. Jason Knight of the University of Michigan and colleagues revealed a promising approach for reducing cells’ release of NETs. Studying mice that are prone to lupus, the researchers tested two compounds — GW311616A and Alvelestat — that block an enzyme called neutrophil elastase needed for cells to produce NETs. Dr. Knight and his team found that mice receiving either GW311616A or Alvelestat made fewer of the harmful antibodies that characterize lupus. In addition, fewer immune cells moved into the animals’ kidneys, causing less damage. These findings indicate that drugs that target neutrophil elastase might work in patients with lupus. See Abstract

A Good Influence on B cells

Previous research has shown that the destructive antibodies in lupus come from immune cells called B cells. Before B cells begin to produce these antibodies, however, they need to be turned on. Dr. John Mountz of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and his colleagues may have identified a molecule that keeps the cells shut off. The researchers analyzed B cells from patients with lupus and found that the cells produced less of a molecule called the interleukin-4 receptor, which functions like an antenna to allow cells to receive messages from other cells. Dr. Mountz and colleagues discovered that if they stimulated the receptor, the B cells did not turn on. The researchers suggest that interleukin-4 receptor could provide a target for developing a new treatment for lupus. See Abstract

Profiling Genes in Lupus Cells

Lupus often results in kidney inflammation, known as lupus nephritis, which researchers can study in mice. If scientists improve their understanding of how different cells contribute to lupus nephritis in the animals, they might learn more about the condition in people. To investigate lupus nephritis in mice, Drs. Nir Hacohen of the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Anne Davidson of the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research and their colleagues measured which genes were switched on or off in kidney, spleen, and immune cells. The researchers now plan to compare their results to results for patients with lupus to identify new cells and pathways that are important for the disease. See Abstract.

“These studies demonstrate how the LRA continues to fund top researchers whose insights are leading to new approaches for diagnosing and treating lupus,” says Dr. Teo Staeva, the LRA’s Chief Scientific Officer.