Recent Discoveries Shedding Light on Why Women Are at a Greater Risk for Lupus

Recent Discoveries Shedding Light on Why Women Are at a Greater Risk for Lupus

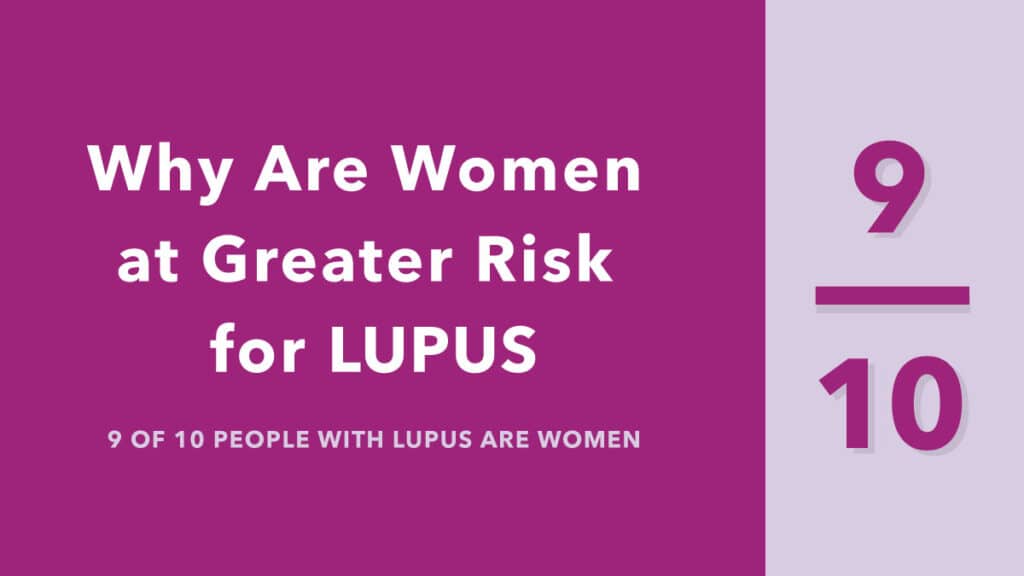

Lupus is a complex autoimmune disease affecting millions worldwide with a staggering gender imbalance — about 9 of 10 people with lupus are women. Underlying biological, hormonal, or environmental factors likely contribute to why lupus affects females more often. Understanding why women are at greater risk for lupus could unlock novel treatments and revolutionize outcomes for all people affected by this debilitating autoimmune disorder. In honor of Women’s History Month, we will recap several groundbreaking findings that have unveiled key insights into the sex bias in lupus and its underlying mechanisms.

Recent Breakthrough on the Role of the X Chromosome

Our chromosomes – carriers of our genetic information — play a key role in the biological differences between females and males. Females typically inherit two X chromosomes (XX), while males usually have one X and one Y chromosome (XY). Within our chromosomes are segments of DNA, called genes, that carry information for making proteins– the “workhorses” of the cell, required for the structure and function of all our cells and tissues. To balance gene expression between females and males and to prevent females from making twice as many gene products (due to their having two X chromosomes), a process called X chromosome inactivation occurs in every cell in a female’s body. This process involves the coating by a molecule called Xist of one of the two X chromosomes to silence it and prevent the potential harmful effects of producing double the amount of X-linked genes.

Howard Chang, M.D., Ph.D., Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Professor of Cancer Research and Professor of Genetics at Stanford, identified 81 proteins that attach to Xist. These proteins, along with the Xist molecule, form what is called the Xist ribonucleoprotein. Many proteins in this complex are known targets of autoantibodies – misguided immune molecules that target a person’s own cell contents by mistake. In a recent study published in Cell, Dr. Chang and his team asked whether the Xist ribonucleoprotein could cause higher rates of autoimmunity in females. Using a mouse model of lupus that impacts females more severely, the team inserted Xist into the genome of male mice (which do not normally make Xist).

Turning on the expression of Xist caused male mice to develop lupus-like features and the kind of extensive organ damage seen more in females. Dr. Chang also found that people with lupus produced autoantibodies that target many of the components of the Xist ribonucleoprotein, suggesting their immune systems are mistakenly reacting to the Xist ribonucleoprotein and targeting its components as foreign invaders. Importantly, these autoantibodies potentially can be used to detect and monitor lupus, enabling earlier diagnosis and treatment. Click here for the press release reporting on this paper from Stanford University.

LRA-Funded Studies Advancing Our Understanding of Why Lupus Targets Women

The LRA has long funded investigators probing the critical question of why lupus occurs so much more often in women. In addition to the important contributions by Dr. Chang, we are highlighting three female researchers funded by the LRA who have also furthered our understanding of the role of the X chromosome in lupus.

X chromosome inactivation is not a permanent process in all cell types. In some immune cells, like T cells, X chromosome inactivation is ongoing and needs to be maintained. In a study funded by the LRA published in the Journal of Autoimmunity, Montserrat Anguera, Ph.D., Associate Professor at the University of Pennsylvania, recently found that the X chromosome may not be sufficiently silenced in T cells of lupus mouse models, particularly in those that affect females more severely. T cells in these female mice showed impaired localization of Xist to the X chromosome and over-production of genes from the improperly silenced X chromosome – many of which have roles in immune function. This high level of immune-related genes produced by the X chromosome may be behind why females are more often impacted by lupus.

While X chromosome inactivation prevents females from producing twice as many gene products as males, some genes on the X chromosome manage to escape this silencing process. With her LRA grant, Laura Carrel, Ph.D., Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Penn State College of Medicine, developed an innovative tool called X-Chromosome inactivation for RNA-seq. In a study published in Genome Research, Dr. Carrel used this new technology to show that genes that escape X chromosome inactivation are linked to diseases like lupus that affect women more often. This further suggests that X inactivation escape could explain why lupus affects more females than males.

With her LRA funding, Alessandra Pernis, M.D., Professor of Medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College and Senior Scientist at the Hospital for Special Surgery, published a study in Nature Communications focused on a subset of B cells called age-associated B cells (ABCs) that increase in older people and at an earlier age in those with autoimmune disease. She found that, in a mouse model of lupus that affects females more frequently, ABCs build up more in females than males. The team discovered a role for a gene called TLR7 in this process, which is located on the X chromosome and has been shown to escape X chromosome inactivation. This also suggests that the X chromosome and immune-related genes that escape silencing may play a role in the higher rate of autoimmunity in females.

“Understanding why lupus affects women more often than men has long been a central question to understanding the disease,” noted LRA Chief Scientific Officer Teodora Staeva, Ph.D. “These key findings are transforming our understanding and could drive the development of more personalized and effective treatments tailored to each person’s needs.”

As we celebrate Women’s History Month, we recognize the invaluable contributions of researchers like Drs. Chang, Anguera, Carrel, and Pernis in advancing our understanding of lupus. We will continue to strive towards a future where all people can live free from the burden of autoimmune diseases like lupus.